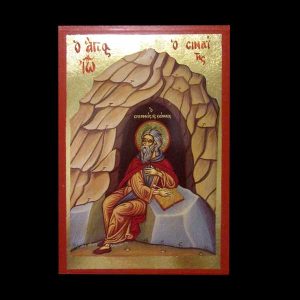

In the early 7th c., John Climacus, abbot of the monastery at Sinai, accepted a request from Abbot John of Raithu Monastery to record soul-profiting monastic wisdom for the brethren.

Saint John compared spiritual life to a ladder, with each of the 30 rungs presenting a different challenge to cast off vices and acquire virtues.

Read during the Great Fast in monastery trapezas and acclaimed by Orthodox laity from its inception.

Hard-cover cloth-bound, 288 pages

From the introduction:

This is the nature of all the ascetical writings of the Church from the earliest times, for monasticism is seen as a consecration of one’s life to God, using all these instructions and words of experience. There are not different monastic “rules” or “orders” in the Church. There is only one rule for all monastics: fasting, vigilance, and prayer, with vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience. But in the West, especially after its separation from the Church, different competing orders arose with different rules set on different courses. The scholastic and rationalistic mentality, which wished everything to be clearly defined, aided in this. And whereas of old, the Fathers expounded to us in what monasticism consisted, now the emphasis was on the how this is accomplished. For the Fathers of the Church, the how is a mystery accomplished in us by the Holy Spirit – it is a whole life of Grace. But for the scholastic mind, it became a systematized rule like a physical exercise, a sort of technique. Yoga and similar disciplines of the far East are akin to this mentality. According to such an understanding if one does this, the outcome must necessarily be that. Yet we know from experience that things in the spiritual life do not work thus, that techniques and rules do not make the monk. Only by keeping up a pretense can one believe that he has thus become a monk. Externally he may appear to be some sort of a monastic, but internally there is a void. And after a time, one abandons even the pretense, and then there is nothing.

Not only for those separated from the Church is this a danger, but for all of us. Thus it is necessary, if we are not to become sterile, to be continually returning to the clear sources of the monastic life, to be studying them and living them. One such great source is the Ladder. So greatly is this God-inspired book esteemed by the Church that its author, Saint John Climacus, is celebrated twice in the liturgical year: once on the day of his repose, which is the 30th of March, and a second time on the Fourth Sunday of Great Lent. In all of the Church’s monastic communities throughout the world, the Ladder is read during the duration of the Great Lent in the refectory during the common meal. This is a period of strict fasting, of prostrations, of compunctionate prayers, when only one meal is partaken of in the day, and this after the ninth hour (3:00 P.M.). After the twelfth hour (6:00 P.M.), even water is abstained from until the meal of the next day, which is again after the ninth hour. Being read therefore during the meals in this period of fasting and struggles, it makes a profound impression on its hearers. And this is exactly how such texts should be read if they are to bear any fruit in us – not in spaciousness and comfort, not sitting in armchairs, eating snacks and sipping soft drinks, but rather with prayers and fasting, with prostrations and sighs. Then verily there is fulfilled the verse of our father, David: “Open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it” (Ps. 80:9).